Rare Editions of Pushkin Are Vanishing From Libraries Around Europe

In April 2022, soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, two men arrived at the library of the University of Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city. They told the librarians they were Ukrainians fleeing war and asked to consult 19th-century first editions of works by Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s national poet, and Nikolai Gogol. Speaking Russian, they said they were an uncle and nephew researching censorship in czarist Russia so the nephew could apply for a scholarship to the United States. Eager to help, the librarians obliged. The men spent 10 days studying the books.

deneme bonusu

Four months later, during a routine annual inventory, the library discovered that eight books the men had consulted had disappeared, replaced with facsimiles of such high quality that only expert eyes could detect them. “It was terrible,” Krista Aru, the director of the library, said. “They had a very good story.”

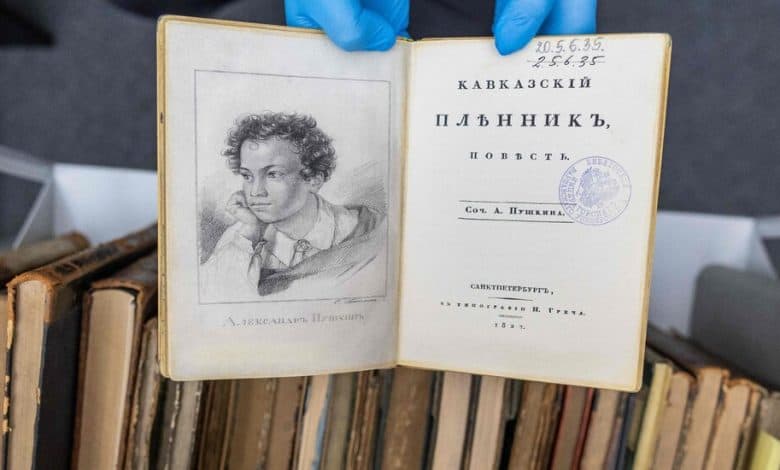

At first, it seemed like a one-off — bad luck at a provincial library. It wasn’t. Police are now investigating what they believe is a vast, coordinated series of thefts of rare 19th-century Russian books — primarily first and early editions of Pushkin — from libraries across Europe.

Since 2022, more than 170 books valued at more than $2.6 million, according to Europol, have vanished from the National Library of Latvia in Riga, Vilnius University Library, the State Library of Berlin, the Bavarian State Library in Munich, the National Library of Finland in Helsinki, the National Library of France, university libraries in Paris, Lyon and Geneva, and from the Czech Republic. The University of Warsaw library was hardest hit, with 78 books gone.

The books are worth tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars each. In most cases, the originals were replaced with high-quality copies that mimicked even their foxing — a sign of a sophisticated operation. The disappearance of so many books of the same ilk from so many countries in a relatively short period is unprecedented, experts said. The thefts have led libraries to boost security and put dealers on high alert about the provenance of Russian books.

How Russian rare books came to be at the center of a possible multinational criminal conspiracy is a story of money and geopolitics as much as of crafty forgers and lackluster library security. Authorities, librarians and experts in Russian rare books believe the thieves are smaller fish operating on behalf of bigger fish. But who is behind the thefts, and what motivates them, remain open questions.

First editions of Russian Golden Era writers have sold for five and six figures in recent years at Western auctions. Experts say there is a thriving market for them today in Russia, where they have tremendous cultural and patriotic value. French authorities have not ruled out a state-sanctioned drive to bring Russian treasures home to Russia.

According to Europol, the authorities have arrested nine people in connection to the thefts. Four were detained in Georgia in late April, along with more than 150 books. In November, French police placed three suspects into custody. Another man has been convicted in Estonia and a fifth suspect is in jail in Lithuania.

A special French police unit dedicated to fighting cultural theft is overseeing the investigation in France and coordinating across Europe. Authorities paint a picture of a network of associates, some blood relatives, traveling across Europe by bus with library cards sometimes under assumed names to scout rare Russian books, make high-quality copies, then swap them for the originals, case files reviewed by The New York Times reveal.

The investigation, dubbed “Operation Pushkin,” was reported in depth by Le Parisien, a Paris daily. The director of France’s culture police unit, Colonel Hubert Percie du Sert, declined to comment on an ongoing investigation.

In Russia, Pushkin is a national icon with the status of Shakespeare but the familiarity of a friend. A Romantic poet, novelist and playwright, aristocrat, libertine, writer on freedom and empire, he brought Russian literature, and the Russian language itself, into modernity before dying in a duel at age 37, in 1837.

“In Russia for the past 200 years, there were not four elements in nature but five, and the fifth is Pushkin,” André Markovicz, the pre-eminent translator of Pushkin into French, said.

Every leader of Russia has embraced Pushkin in line with his own political vision, from the czars who expanded the Russian empire in the 19th century, to Stalin — who held public celebrations across the Soviet Union on the 100th anniversary of Pushkin’s death in 1937 even while purging intellectuals — to President Vladimir V. Putin, who has cited Pushkin in speeches and unveiled monuments to him around the world.

“Pushkin is the mirror of all the epochs of Russia,” Markovicz said. In Ukraine today, Pushkin has become a reviled symbol of Russian imperialism since the brutal Russian invasion and people have toppled statues to him.

Prices of books published during the lifetimes of the holy trinity of Russian Romantic writers — Pushkin, Gogol and Mikhail Lermontov — have risen dramatically in the past 20 years, in line with the rise in wealth of Russian collectors. It’s a small market with relatively few books and collectors who often have a checklist of the books they want, dealers say.

Pushkin died young and so “lifetime” Pushkins are scarce. He published “Eugene Onegin,” a novel in verse, as a serial; a first edition with some chapters in their original wrappers sold for more than 467,000 British pounds ($581,000) at auction at Christie’s in 2019.

Western sanctions put in place after Russia invaded Ukraine prohibit dealers in the West from selling to residents of Russia, fueling an existing shadow market for rare books. In this market, sales are often brokered privately through middlemen, with cash transactions that are difficult to trace, dealers say. Libraries are easy targets for thieves because they are intended to serve the public; they are often underfunded, without the same security as museums and other institutions with valuable works.

“It’s easy to get the books, it’s easy to know which books you should get and it’s easy to know the value,” Pierre-Yves Guillemet, a dealer in London specializing in Russian rare books, said.

Guillemet and other dealers said it would be unlikely for the Russian books stolen from European libraries to turn up at official auctions in the West. The International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, a trade organization, has listed many of the recent library thefts on its Missing Books Register.

Angus O’Neill, the group’s vice president and security chair, said the organization had been in regular contact with Europol to inform its members about the thefts. “Booksellers are advised to be cautious!” the State Library of Berlin wrote on the Missing Books Register, listing the five Russian books it had lost, with a total value in the low six figures.

Absorbing so many stolen books into the relatively small market for Russian books could be difficult. But these are the most famous books in Russia, Guillemet said, potentially attractive not only to seasoned collectors, but also to “rich people wanting trophy items.”

Europol said some of the stolen books had already been sold by auction houses in Moscow and St. Petersburg, “effectively making them irrecoverable.” The agency did not reveal which books, citing the ongoing investigation.

Dealers say it is not uncommon for Russian books with library stamps to be for sale. The Soviets plundered private family collections and nationalized libraries. During the Second World War, libraries burned, the Soviets took books from Germany and the Nazis took books from Russia. When the Soviet Union was collapsing, impoverished librarians sometimes sold library books on the sly to support themselves.

In the 20th century, Russian books flowed westward as émigrés sold their collections. In the 21st century, they flowed eastward as new generations of Russians bought them back. In 2018, Christie’s auctioned one of the largest private collections of Russian books in the West, amassed by R. Eden Martin, a lawyer in Chicago, a sale that totaled more than $2.2 million.

The recent thefts have led to heightened vigilance. “It’s deeply upsetting whenever thefts like these occur,” Susan Benne, the executive director of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America, said. “Libraries are in the business of providing access to scholars and the public, and when a breach of trust like this occurs, necessary changes in security can curtail that access.”

The thefts seem to have caused the most public outrage in Poland, which is acutely sensitive to actual and perceived Russian aggression. Last October, the library of Warsaw University, a former Russian imperial university with a large collection of 19th-century Russian books, discovered 78 Russian rare books missing, including first editions of Pushkin. The thefts may have begun in the fall of 2022 and continued until they were discovered 10 months later, a spokeswoman for the university said.

As authorities across Europe begin to arrest suspects, so far all of them Georgian nationals, a picture is emerging of a possible network. One of the men implicated in thefts at Vilnius University Library, which lost 17 books valued at 440,000 euros ($470,000), is in jail in Lithuania. He is also suspected to be involved in library heists elsewhere, according to case files reviewed by The Times. In Estonia, one man was convicted on charges related to the Tartu heist. He had been extradited there from Latvia, where he served time for facilitating the theft of three books from the National Library of Latvia in Riga — one by Pushkin and two by the Russian Futurist poet Aleksei Kruchyonykh, who, as it happens, renounced Pushkin and sought a new poetic language.

Last November, French police placed three people into custody on charges of criminal conspiracy for stealing 12 Russian books at a university library in Paris, the Paris prosecutor’s office said. It said authorities had linked the alleged culprits to another theft last July at the library of a prestigious public university in Lyon. The same men had also been identified at the National Library of France in Paris, according to case files seen by The Times.

These days, requesting a 19th-century early edition of Pushkin in the rare books room of the National Library of France will draw nervous looks from librarians and swift requests for further information about a reader’s motives. Last year, thieves lifted eight books by Pushkin and one by Lermontov, with a total estimated value of €650,000 ($696,500), one of the largest thefts from the library in the modern era.

The pattern was the same. A man showed up over a period of months to consult rare Russian books. When librarians asked the nature of his research, he claimed not to speak French or English. The librarians were doubtful, but ultimately gave him access. The man allegedly stole the books, possibly hiding them in the sling of a bandaged arm. He replaced them with such high-quality copies that librarians didn’t discover the thefts for months.

The library now keeps its Russian Golden Era books in its holy of holies, along with its rarest books, including a Gutenberg Bible.